509 views Women in the World of the Yakuza: Hidden Power or Silent Victims?

When most people think of the Yakuza, a rigid hierarchy of men in crisp suits, underground deals and neon‑lit nightclubs comes to mind. Yet beneath that masculine façade lies a complex web of female involvement that history and contemporary culture have only begun to fully understand. Are women merely silent witnesses, trapped in the shadows of male dominance, or are they quietly shaping the organization’s decisions from within?

The Early Days: Women in the Yakuza’s Formative Years

The origins of the Yakuza trace back to the Edo period, when teishō-giri (claw‑paying) adolescents would pickpocket tavern patrons. Some of these early gangs embraced women as associates, although they were largely relegated to peripheral tasks—carrying gear or acting as gossip conduits. As the 19th century progressed, women began to assume okiya (hostess) roles, serving as barmaids and brothel workers whose money belonged to the syndicate’s leaders. In this era, few women recognized themselves as members; they were largely pawns in a patriarchal system.

Traditional Roles: Service, Loyalty, and the “Ozōri” Mask

The stereotypical image of a Yakuza wife or mistress carries with it a sense of fragile trust. Ozōri, female figures who serve as in‑house confidantes, are expected to be devoted to their male counterpart, vetting suspects, and securing loose ends. These women rarely wield decision‑making power, but they possess an often‑underrated strategic influence. Their intimate knowledge of family networks can crack rival factions shut or, conversely, leak critical information to law enforcement.

Key Traditional Functions

- Property Management: Women often managed commercial real estate, enabling the syndicate to launder profits.

- Mediation: As neutral parties, they brokered feuds between rival groups, preventing costly violence.

- Information Brokerage: They were the first line of reception for cults or mysterious clients, filtering out threats.

Despite the socioeconomic respect they earned in certain districts, prostitution and statutory abuse laws had a heavy toll on these women’s lives.

Beyond Servitude: Women Who Walked the Ranks

The 20th century brought sweeping changes to Japan’s social fabric, and the Yakuza were no exception. During the post‑war occupation, women found themselves caught in shifting labor dynamics and an economy hungry for illicit enterprise. Many slipped from the shadows to become actual executives, owners, and sometimes enforcers.

- Shōko Kuroda, a former oko who rose to become a senior accountant for a Sō–kan, was instrumental in diversifying the syndicate’s interests into real‑estate and auto‑parts.

- Kazuo “The Hammer” Tanaka’s wife, Mariko, ran the front‑office operations, coordinating tax‑evasion schemes that spanned the Pacific.

These women had to navigate a space where gender stereotypes clashed with financial acumen. Their rule‑breaking stories highlight that, contrary to mainstream narratives, female members could muster their own leadership styles, often rooted in negotiation speed and empathy.

The Silent Victims: Abuse Hidden Beneath Glitter

Not all women’s journeys with the Yakuza were upward marches; many were consigned to positions that extracted them from society’s core. The syndicate’s rigid code—ninkyō (honor) and giri (obligation)—could become a cage. Physical coercion, forced marriages, and sexual exploitation are stark realities documented in court transcripts and survivor testimonies.

- Forced Marriages: Young women were paid a pat on the head to marry a senior boss, promising a “stable future.”

- Silent Allegations: Victims often recanted due to fear of retribution or financial leverage from the syndicate.

- Fatalities: In some cases, women were eliminated when they attempted to break free or threatened to expose crimes.

These incidents illustrate that the Yakuza’s power structure is double‑edged. High visibility leaders are rarely scrutinized, whereas those at the bottom carry the brunt of violence.

Gender Versus Power: A Macro‑Perspective

When we overlay gender on the Yakuza sphere, we see an ecosystem where power is fluid, often negotiated through interpersonal networks rather than legal structures. Women’s influence is amplified in familial connections—especially when they are mothers or daughters of top-ranking actors. In many cases, this power is exercised gently: cutting off rivals through a quiet email or whispering a warning on a business card.

The phenomenon of seibun (silent but strong) leadership—women who appear passive on the surface but coordinate covert operations—is key to understanding how the Yakuza operates in a globalized economy. Thus, gender alone does not dictate power; the intersection of lineage and opportunity does.

Reforms, Law Enforcement, and the “Hōkō” Shift

In the last two decades, Japanese law enforcement has approached the Yakuza from a gender‑sensitive perspective. The “Hōkō” (Narcotics Enforcement) crackdown reshaped how women are perceived: from silent facilitators to active conspirators, they have been sentenced to prison terms specifically for orchestrated racketeering.

- 2019 Amendments to criminal code expanded sanctions for feminine participation.

- Public Awareness Campaigns showcased female survivors, encouraging whistleblowing.

- Civil Rehabilitation Programs provide exit pathways for women who wish to leave the underworld.

While reforms unevenly hit the organization, they have made it clearer that the Yakuza’s gendered roles are not static.

Highlight: Women Who Left the Shadows

Fumiko Yamada: Once a junior staff in Tokyo’s makai (underground casino), she left the network after witnessing forced labor. In 2015, she authored Silver Songs of the Yakuza, a memoir that goes from the inside to an activist voice.

Eri Shimamoto: She founded a non‑profit that finances legal defense for women with Yakuza ties, rewiring how society sees “criminal women.”

Such cases underline the fact that quitting is possible—alone, or with external help.

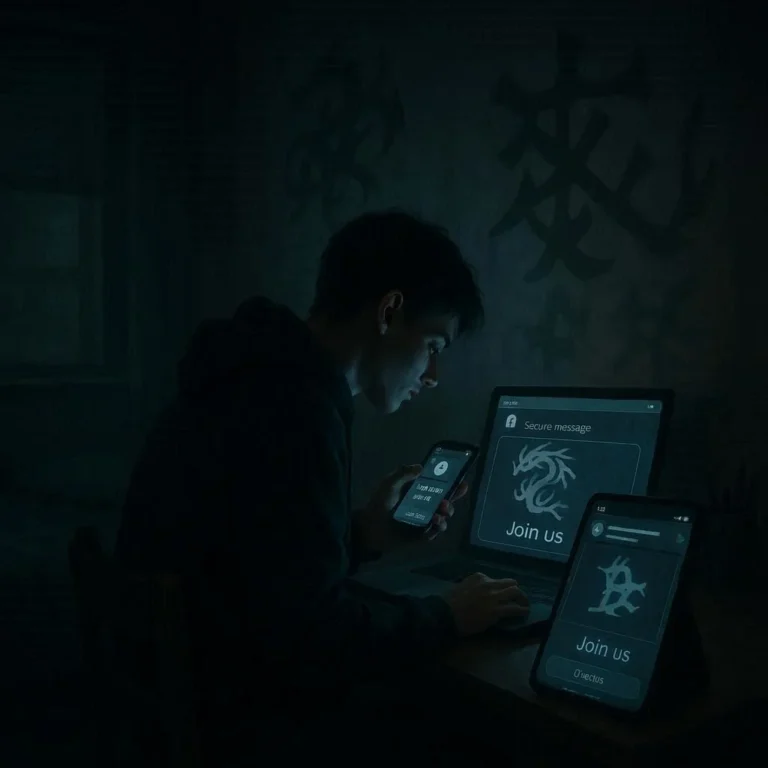

Liminal Spaces: Media, Anime, and Hollywood

Modern pop culture—particularly anime, manga, and Hollywood films—has both romanticized and demonized female Yakuza roles. The trope of the “in‑law” becomes a double‑edged sword: a wealthy advocate who manipulates behind the curtain versus a victim of forced allegiance. The representation trend shifts, suggesting growing public interest in the nuanced stories of these women.

Examples to Note

- Yakuza : The Code of the Street (1995 movie) portrays a village matriarch who defends her village from an organized crime takeover.

- The anime series Blade of the Border (2021) features a female kūmon orchestrating covert operations.

These portrayals influence public perception, but they are often simplistic. Critics argue that the queer, psychological aspects of female power remain under‑explored.

Conclusion: A Spectrum, Not a Verdict

The Yakuza picture is no longer a binary portrait of men versus women. Women in its world embody a spectrum: some hold clandestine power, others are silent victims, yet more swing between the two. Historical context, economic diversification, and evolving societal norms collectively modulate how they are perceived and how they are coped.

For anyone studying organized crime, the crucial lesson is that gender must not be treated as a mere footnote but as a strategic variable.