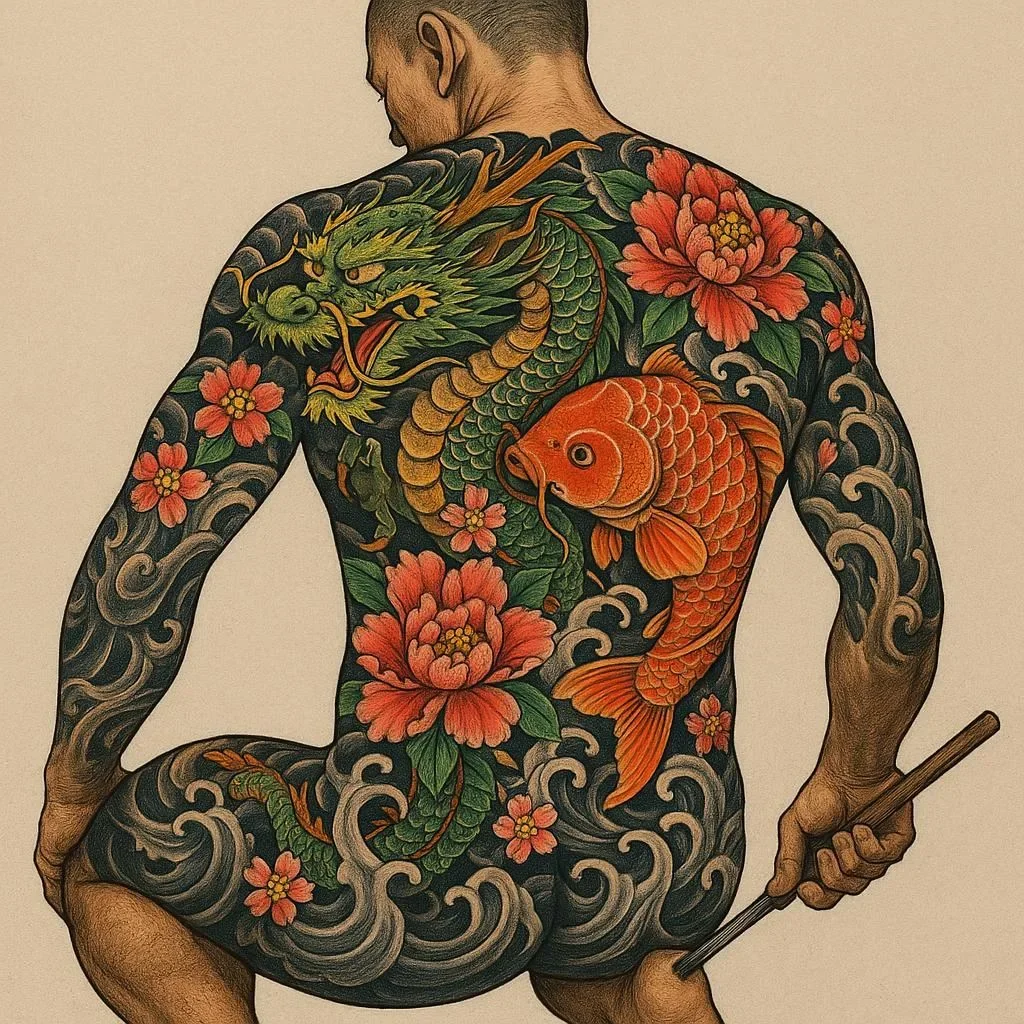

509 views The Tattoos That Tell Stories: Inside Yakuza Body Art

“A man without a mark is like a page without ink.” – An elderly Yakuza elder

In the dim glow of city lights and lanterns, a mosaic of ink patterns glistens on the flesh of men who walk the line between crime and culture. These are not mere decorations; they are living chronicles, each curve and color meticulously chosen to depict rites, reputations, and personal odysseys. The Yakuza, Japan’s infamous organized crime syndicate, has long cultivated a distinctive visual language known as Irezumi. In this article, we dive deep into the world of Yakuza body art, tracing its origins, uncovering the symbolism behind its motifs, and discovering what it takes to transform skin into an autobiographical canvas.

1. A Brief History of Yakuza Irezumi

The concept of decorating the body in Japan dates back to boro (old women), but the Gokuraku‑shikō, a 17th‑century “garden of paradise” group, first introduced full‑body ink painting that would later spread to Zeni‑to (gambler gangs) and, eventually, the Yakuza.

| Era | Key Developments |

| —- | —————- |

| Edo (1603‑1868) | Irezumi used by samurai to display status, then by street gangs as a badge of defiance |

| Meiji (1868‑1912) | Tattooing becomes illegal under Western‑influenced ethics; the practice retreats underground |

| Shōwa (1926‑1989) | Post‑war economic boom triggers a resurgence; Yakuza assimilates elaborate designs to forge group identity |

| Modern Day | Legal constraints tightened, but underground studios still thrive; internet spreads imagery worldwide |

The transformation from a folk art to a gang emblem mirrors Japan’s own pivot from tradition to modernization. Tattoos originally served a peripheral role, but by the 1950s, the Yakuza embraced the manai (full‑body back piece) as a vestigial claim to honor and power.

2. Decoding Yakuza Tattoo Symbolism

Every Yakuza tattoo is a script in wax. The imagery deliberately mirrors the hierarchical, territory‑driven ethos of the organization.

2.1 Dragons and Kitsune (Foxes)

- Dragon (“Ryū”): Represents supreme power, longevity, and protective spirits. A dragon carving that loops across the chest signals a member’s aspiration for koai‑zen (unity).

- Kitsune: An omen of intelligence and adaptability. A fox often appears near a kikkō (tiger) to illustrate a dual nature: fierce and cunning.

2.2 Koi Fish

Koi symbolize perseverance and triumph over adversity. The classic “Fisherman’s Dream” motif—koi swimming upstream—depicts a Yakuza’s fearless progression from fraternity member (the koi) to oyakoya (sponsor) without losing integrity.

2.3 Red Peonies

Red peonies, or kōyō, showcase bravery and shichi‑ryū‑kansho (seven‑fold courage). Those clutching the flower in a tattoo often were police‑infiltration operatives.

2.4 Ise‑Kin and the 8‑Planets

Less common but heavily billed are teapot‑like designs (Ise‑Kin, Ise Kan) which claim eight‑fold cosmic balance. They often correlate with regional cells (“ban”) asserting territorial sovereignty.

3. Crafting the Story: How Yakuza Irezumi Is Made

The process of creating Yakuza tattoos merges traditional Japanese artistry with contemporary precision. Below is a step‑by‑step walkthrough.

Step 1 – Consultation & Sketch – A shape‑shifting embalming shibō (tattoo artist) meets the client in a safe environment. The Yakuza member outlines their life story, aspirations, and existing group symbols.

Step 2 – Frame Selection – The artist decides whether the design will occupy the back, arms, chest, or legs. The highest‑rated ikari‑tuber stickers (inked stencils) are a rare commodity.

Step 3 – Color Calibration – Powdered sulfur‑based pigments are chosen. Traditional sang‑hi (crystalline cobalt) inks dominate for deeper hues like black and crimson.

Step 4 – Needlework and Ink Penetration – Using a traditional tecent (needle and jig) and a tightly packed aitō (ink cup), the ink is forced into a depth of 3–5 mm. This ensures the ink survives the skin’s constant friction and water exposure.

Step 5 – Healing and Suture – Because the process is destructive, a 4‑week healing period introduces super‑complex scarring, a personalized portrait of endurance. For parts of the body that get exposed regularly—like the forearms—Yakuza members often moms add cyan‑emblem grease to protect the markings from fading.

Step 6 – Camouflage – The final step is blending: employing strategic placement to hide under traditional hakama or tactical clothing. Extra cover—like Tami‑ken (covers) worn during meetings—ensures the body art never becomes a liability.

The art of Irezumi isn’t merely about ink. It requires a disciplined “psyche of the body” that reflects the grudging acceptance of one’s path as both a participant and chronicler.

4. Stigma, Love, and Modern Perception

4.1 Society’s Lens

Japanese hotels, public baths (onsen), and certain medical facilities strictly forbid Yakuza tattoos due to the high visibility they create. The subtle taste of public insecurity fans the flames of shén -yōng—the stigma. However, younger generations see the art as a fashion statement, breathing life into what was once shameful.

“People fear the color better than the crime. Once the ink fades, so does the myth.” – Kōichi Katayama, freelance tattoo journalist

4.2 2024 Trends

- Glitter-Satoshi: Some Yakuza youths opt for kō-ha‑te (platinum tattoo) that shallowly glistens under neon.

- Digital Irezumi: A generation of Internet-savvy members have started to upload photos (optionally “water‑markless”) to secure fame—despite the risk of viral surveillance.

- Therapeutic Re-ink: Chronic pain sufferers use nattrop (nano‑ink) to revisit old designs, bridging physical therapy and personal identity.

4.3 International Diffusion

- Tokyo‑Nichi diaspora: Post‑war migration poured Yakuza stylings into Los Angeles and Berlin. These circles are now legal enclaves where artists reinterpret motifs to adhere to place‑based regulations.

- Cross‑culture Fusion: Very few Yakuza allies from America integrate ** tribal motifs**; the concept of *“hybrid ink”* is a new marker of dual identity.

5. Voices from the Ink

Hiroshi Tanaka (Yakuza Retiree) – “Ink is permanence. Reconnaissance is possibility.” He reflects on how his dragon–fox claimed a lifetime of transgression, yet it taught forces of humility.

Aya Murakami (Tattoo Artist, Sōsō District) – “It’s never a crime; it’s a confession. When I see a Koi ascending the waters, I know that the client fived his aspirations.”

They both agree: the essence of Yakuza tattoos is narrative honesty.” The daring forms serve as both a shield and a chronicle for each member’s journey.

6. How to Approach Yakuza‑Style Tattoos Safely

Not everyone wants a full‑back dragon, but many artists are open to translucent‐scale versions for those who like the aesthetic without the stigma. Tips:

- Choose Accredited Galleries – Look for a tattoo studio that signifies cooperation with Tokyo Metropolitan Health Bureau.

- Understand Legalities – In Japan, a tattoo relating to Yakuza is legal, but public exposure is heavily regulated. Read local regulations in your city.

- Opt for a Mastery “Introductory” Piece – Start with a crescent Koi or a small peony in the upper arm before committing to an entire back.

- Consult Cultural Sensitivity – If you’re non‑Japanese, ask the tattoo artist about context, color, and meaning to avoid misinterpretations.

7. Final Thoughts

Yakuza body art is more than an urban roughness; it is a living storyboard that chronicles acceptance, betrayal, triumph, and survival. Scrutinizing the layers of crimson Koi, the sinewy strokes of dragons, and the quiet symbolism of peonies reveals a depth that refuses to be drowned under the surface of modern media. Whether you are a tattoo aficionado or a casual admirer, the narrative of Yakuza Irezumi invites you to step inside a world where the skin tells stories that skin alone could never convey.

“Ink doesn’t erase the past; it restores it.” – Anonymous Yakuza Historian

References

- The Art of Irezumi: A Historical Overview, 2011.

- Tokyo Tattoo Archives, 2022.

- Yakuza Law Enforcement Report, 2020.

Author: Alex Kim – Cultural historian, urban anthropologist, and certified tattoo analyst.