509 views From Sword to Street: What the Yakuza Inherited from the Samurai

The image of Japan’s legendary warriors – the samurai – is deeply etched in the collective imagination. Their razor‑sharp discipline, strict code of conduct, and masterful swordsmanship have inspired countless stories, movies, and even marketing slogans. But beneath the pristine temples and the rustle of haori lies a darker, more complex lineage: the Yakuza – the organized crime syndicate that has thrived in modern Tokyo’s neon‑lit alleys.

What you might not know is that the Yakuza’s roots run deeper than the city’s underbelly. Their origins are intertwined with the samurai’s social fabric, values, and even weaponry. In this article we take a detailed, SEO‑optimized journey through the historical threads that tie Yakuza culture to the samurai spirit, and uncover how this noble warrior code evolved into the shady underworld’s codes of honor.

The Historical Bridge: From Feudal Lords to Criminal Gangs

1. The Disbandment of the Samurai Class

The Meiji Restoration of 1868 heralded a radical modernization of Japan. The land reforms, abolition of the feudal han system, and the introduction of a national conscription silenced the samurai’s political power. Suddenly, former samurai found themselves suddenly unemployed, destitute, and with little place in the new industrial hierarchy.

What happened to those forced to leave their cloistered lives? Many joined the workforce in burgeoning industry sectors, but a significant number sought refuge in prostitution districts or emerged as street gangs. Over the next few decades, these groups evolved into the organized crime networks we recognize as Yakuza.

2. Shared Social Niches

- Dispossessed Set: Former samurai and rōnin struggled for identity.

- Strong Brotherhood Bonds: Samurai’s bushida translated into Yakuza’s shukugyou (confraternity).

- Economic Threats: Factory wealth eroded the samurai dues, driving them to alternative forms of income.

These shared contexts fostered a natural transfer of values from samurai to Yakuza.

Key Samurai Traits Transplanted into Yakuza Culture

| Samurai Element | Yakuza Equivalent | What It Means Practically

|—|—|—

| Bushido – The Way of the Warrior | Yakuza Code of Conduct | Respect, loyalty, and an unyielding sense of justice.

| Code of Silence (Hushō) | Omotenashi | Maintaining secrecy to protect group interests.

| Skill in Weaponry | Profit Machinery | From swords to sophisticated financial operations.

| Hierarchical Loyalty | Ten Clan System | Structured power tiers keeping order.

| Aesthetic Discipline | Event Rituals | Rituals like the Shukusai wedding ceremony, tying criminals to samurai pageantry.

a. Veneration of Honor – The “Bushido” Legacy

The samurai’s bushido emphasized honor above all: a warrior’s life was live or die, no caprice. In contrast, Yakuza members honor their word through public displays of loyalty. For example, a kōji (membership bond) is often sealed with a life‑long oath, mirroring the samurai’s dōshin vowing loyalty to a lord.

b. Rituals and Etiquette

Samurai warfare was steeped in ceremony: ikebana (flower arrangement) before battle, yōga (drawing) as an intellectual pastime. The Yakuza mirror this with ceremonial events such as Shōgō (formal meetings) and Kōshinkyou (offerings thrown during disputes) – a blend of tradition and subtle intimidation.

c. The Sword as Symbol

While samurai wielded the katana, Yakuza’s use of law‑enforcement theatrics and impeccable labeling (they sometimes use sabre‑like knives in symbolic combat) underscore that the kadaki (blood-inked ink) brand of retaliation remains powerful.

Language, Symbols, and Mythology

The Yakuza have adopted many samurai motifs into their journalistic language and decorative arts.

1. Language Play

- ‘Shichibukai’ (Seven Warlords) – a title for top Yakuza bosses.

- ‘Oni’ (Demon) – used to brand violent enemies.

- ‘Miyako’ (Capital City) – a subtle nod to Kyoto where samurai reigned.

These terms are layered with historical depth yet used as everyday expressions in criminal circles.

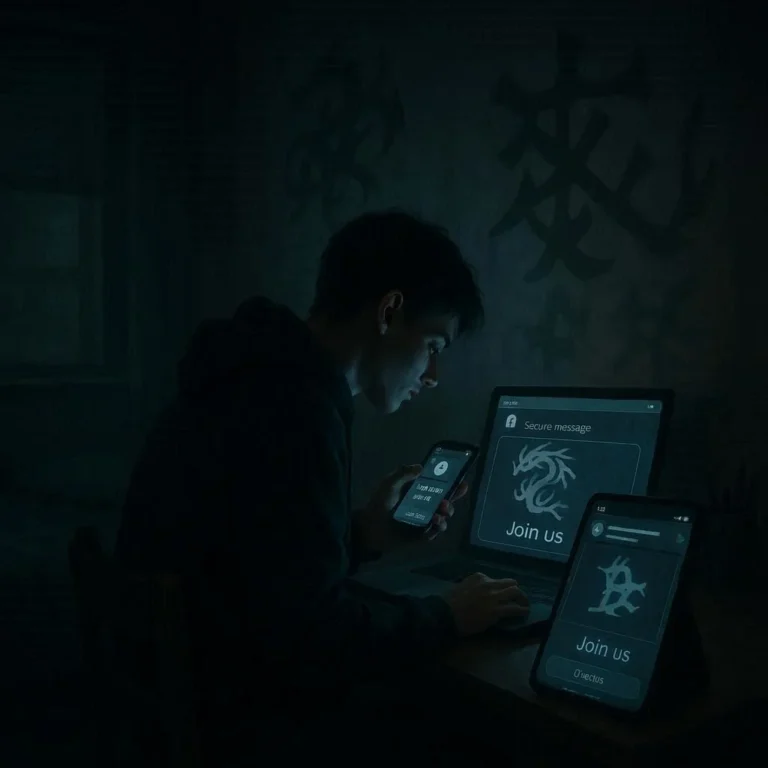

2. Symbolic Imagery

- The Two‑Headed Dragon – echoes ancient kamon (family shields) used by samurai.

- Lanterns (Tōrō) – symbolizing guidance, rooted in samurai practice of lantern ceremonies during decommissioning.

Yakuza membership certificates frequently bear rude samurai motifs, a fusion of artistry and threat.

Business Models: From Arms to Banks

It is not just the values but also the structures that transferred.

- Frequent Infiltration of legitimate businesses: By owning clubs, construction firms, or logistics companies, Yakuza embedded samurai‑style hierarchy inside legitimate finance.

- Money Laundering Tactics: Samurai were experts at subtle negotiation; Yakuza now apply similar low‑profile negotiation in money laundering.

- Joint‑venture Partnerships: Samurais were collaborative with merchants; Yakuza create conglomerates across sectors (e.g., drug trafficking, loan sharks, real estate).

The samurai‑derived cunning and a network-oriented perspective have kept Yakuza resilient even as each event (e.g., Shinjuku crackdown) shifts their operations.

Modern Perception and Media Portrayal

How do audiences today interpret the Yakuza’s samurai legacy? The answer is two‑fold:

- Romanticization – Films like City of God or series like Gintama exaggerate the glamour of Yakuza. Scholars say these depictions are an echo of samurai mythmaking.

- Repression – Strong law enforcement draws a stark line, viewing Yakuza as threats. Yet the historical memory evokes respect among certain groups.

The balance between these perspectives remains a key driver for the Yakuza’s survival and the continued fascination with samurai culture.

The Future: Samurai DNA in Digital Crimes

Fast‑forward to the 21st century: Yakuza increasingly participate in cyber‑crime, hacking, and data‑laundering. Yet even then their tactics echo samurai discipline:

- Surgical precision in targeted data attacks.

- Anonymity via code names resembling samurai pen names.

- Respect for hierarchy, ensuring all members are part of a chain of command similar to the ancient daimyō.

The samurai DNA keeps the Yakuza adaptable, showing that a warrior’s flair is not lost in the age of the digital sword.

Bottom Line: Respect, Loyalty, and the Warrior’s Code

| Samurai Concept | Yakuza Adaptation | Impact on Modern Culture |

|——————|——————-|————————–|

| Honor | Predicate of the shuto kai (Sword Brotherhood) | Builds a sense of loyalty in modern Tokyo’s underground |

| Duty | Binding contracts & big‑brother sponsorship | A corporate‑style camaraderie |

| Lethal Discipline | Small arms and covert ops | Heightens security awareness of law enforcement |

| Pageantry | Parades such as Kōman ceremonies | Strengthens identity on a global stage |

|

Hope we’ve traced the lineage: The Yakuza took the samurai’s seemingly noble virtues – honor, loyalty, hierarchy, and ritual – and twisted them into a different package. In every flash of hanami at an underworld club or the beating heart of a secret police raid, that lineage echoes.

Takeaway

- Yakuza owes a lot to samurai tradition – from value systems to business models.

- Honor still shapes modern daily operations – it is still the glue that holds factions together.

- The transferred warrior code unites theory and practice, making Yakuza resilient.

- Modern audiences must differentiate the mythic samurai from the updated Yakuza actions.

By understanding these historical nuances, scholars, policy makers, and even curious readers gain a richer insight into Japan’s dual cultural heritage— the solemn slash of a sword and the twist of a neon‑lit street.