509 views From Tatami to Temples: A Journey Through Japan’s Aesthetic Sense

Japan’s aesthetic sense is not just a collection of art pieces or a handful of iconic landmarks—it is a living philosophy that weaves together every aspect of daily life. From the humble tatami mats that line a traditional washitsu to the serene stone pathways leading into Kyoto’s ancient temples, an understated elegance permeates all corners of the Japanese experience.

In this blog, we’ll trace the thread that connects Japan’s physical spaces, crafts, food, and spiritual practices, revealing why this aesthetic continues to captivate travelers and creatives around the world.

1. Tatami: The Foundation of Japanese Living Spaces

The Tangible Symbol of Simplicity

Tatami mats, traditionally crafted from rice straw and woven straw mats topped with soft cotton, form the floor of Japanese homes and temples alike. Their uniform dimensions—approximately 0.9 m × 1.8 m—act as a measurement unit in design, allowing architects and interior designers to create harmonious spatial proportions.

The use of tatami is more than a structural choice; it is an expression of Wa (harmony) and Kanso (simplicity). A living room that adheres to tatami rules feels balanced and calm—the perfect backdrop for daily rituals such as tea ceremony or zazen (seated meditation).

Impact on Visual Culture

In films, photography, and fashion, tatami often signals authenticity and a return to traditional roots. The clack of silk slippers on a wooden floor, the soft glow of natural light filtering through shoji screens—these visual cues create an immersive narrative of an aesthetic that values deliberate, modest beauty over ostentation.

2. Core Aesthetic Concepts: Wabi‑Sabi, Ma, and Ikigai

Wabi‑Sabi – The Art of Imperfection

The concept of Wabi‑Sabi celebrates impermanence and the beauty of natural decay. Think of a terracotta pot with a missing shard or a tea bowl that has faint scratches from years of use. These blemishes are not flaws—they tell a story of time and usage, reinforcing the idea that the true value of an object lies in its worn history.

Travel writers often describe Kyoto’s Kiyomizu‑dera courtyard as an embodiment of Wabi‑Sabi: the exposed beams of wood, the weathered stone steps, and the undulating mist all combine to create an atmosphere that feels both ancient and alive.

Ma – The Space Between

Ma, the Japanese word for “gap” or “interval,” refers to the intentional void that accentuates the presence of objects or environments. In Japanese gardens and temples, ma is just as visible as the plants and stone. It encourages mindfulness and reflection, allowing visitors to appreciate the delicate balance between elements.

3. Architecture: A Living Canvas

Traditional Shoin-zukuri and the Flow of Rōnō

Shoin‑zukuri, a style of architecture found in Edo‑period manor houses, showcases floor-to-ceiling tatami rooms, tokonoma alcoves for displaying art, and low wooden beams that reinforce ma. The seamless flow of rōnō (transition) allows a person to move from sitting to standing, dining to contemplation, all while remaining connected to the same aesthetic framework.

Modern Japanese Design

Contemporary architects like Tadao Ando and Yoshio Taniguchi blend these principles with clean lines, minimalist material palettes, and a deep reverence for natural light. Their works—famous for their “empty space” concepts—continue the heritage of ma, proving that traditional aesthetic can co‑exist with forward‑thinking innovation.

4. Gardens: The Philosophical Landscape

Japanese gardens are not merely decorative; they are living philosophical statements. Karesansui or “dry landscapes” use stones, gravel, and moss to imitate mountains and flowing water—each element is a symbolic gesture rather than realistic representation.

In Kyoto’s Ryoan‑ji, the famous 15-stone pond rests upon a bed of carefully raked gravel, forming patterns that shift with every angle of sight. The viewer is encouraged to adopt a contemplative stance, letting the garden’s ma guide inner reflection.

5. Traditional Crafts: The Artisan’s Mindset

From kintsugi (golden repair) to yarn dye (shibori), Japanese artisans apply aesthetic principles to everyday objects. In kintsugi, cracks in a ceramic bowl are patched with lacquer mixed with gold, creating a piece that celebrates damage as part of a richer narrative—a tangible expression of Wabi‑Sabi.

Other crafts—like washi paper, byōbu screens, and lacquerware—merge materials with philosophy, turning everyday utensils into instruments of aesthetic mindfulness.

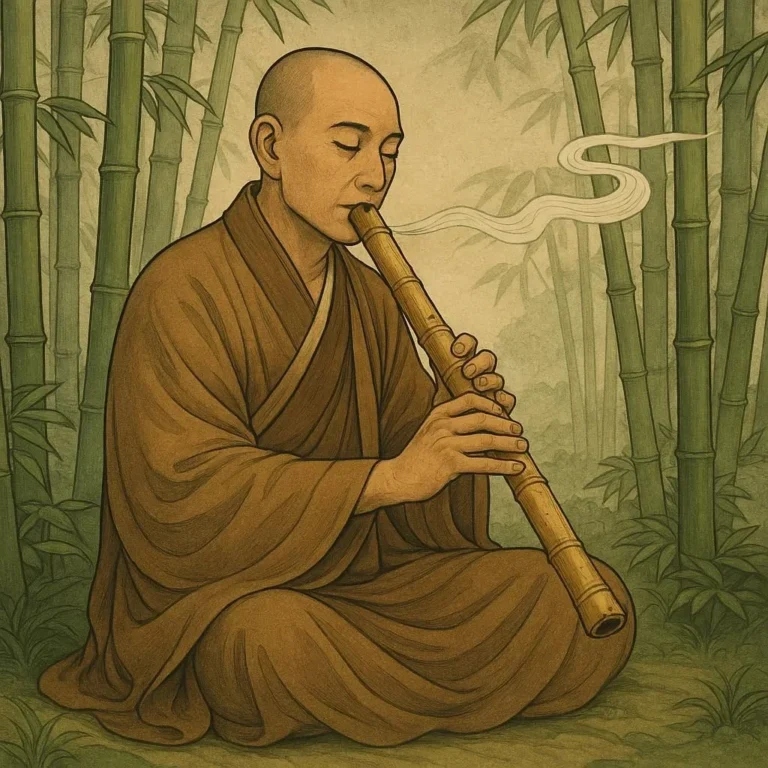

6. Tea Ceremony: Ritualized Aesthetic Practice

The Japanese tea ceremony (chanoyu) is perhaps the most celebrated cultural event that embodies aesthetic philosophy. The ceremony unfolds in a chashitsu—a small tea house with tatami flooring and a tokonoma—where each movement, from wiping the flour dust off the table to delicately placing matcha powder, follows a script that values restraint, presence, and respect.

The subtle interplay between taste, sight, and the subtle sounds of pine wood shrieking as a pot of cha is steeped demonstrates how Ma and Wabi‑Sabi are lived, not merely observed.

7. Culinary Aesthetics: The Senses in Harmony

Japanese food is celebrated for its minimal, seasonal flair. The tradition of washoku—Japanese cuisine—value in Kaiseki dining, where each dish is a visual and tactile expression of era, region, and season. Food is arranged to showcase natural colors, textures, and the interplay of nori (seaweed) or aji (pickles). The entire kaiseki experience is an edible extension of the aesthetic world map.

8. Temples: Spiritual Sanctuaries that Mirror Aesthetic Principles

Classic Buddhist Temples in Kyoto

Kyoto’s temples—Kinkaku‑ji (the Golden Pavilion), Ginkaku‑ji (the Silver Pavilion), and Tenryu‑ji—are masterpieces of aesthetics. Each is a complex system where architecture, gardens, and altar arrangements are carefully orchestrated to foster a contemplative atmosphere.

The Golden Pavilion dominates its surroundings with a gleaming reflection in the pond, epitomizing Shining-order (Shōwa-rin) while the surrounding moss garden teaches the ideas of Kōyō (older Japanese). The entire layout emphasizes ma by creating a path for reflective walking.

The Lotus of Zen

Many Zen temples, such as Enryaku‑ji on Mount Hiei, embody the Wabi‑Sabi principle in their open layout. The unadorned stone walls, the simple oratory Zabuton seating, and the low, wooden gohei beams underline the “less is more” philosophy practiced by Zen monks, echoing the idea that one can find profundity in simple objects.

9. The Modern Evolution and Global Influence

In London’s Kensho boutique hotel, the Wabi‑Sabi ethos has found fashionable resonance in interior design, blending tatami-like flooring with contemporary seating and art. Similarly, the deconstructivist architecture of the Rokko tower, located in Osaka, pays homage to ma through directional light play, reflecting viewers’ impressions of its structured voids.

Japan’s Aesthetic Packaging influences global consumer products. For example, the Tokyo International Peace Bell Project exemplifies kaizen (continuous improvement) and Wabi‑Sabi, turning everyday objects into symbols of regional peace and heritage.

10. How To Experience Japan’s Aesthetic Sense

- Walk the Paths of Kyoto’s Temples: Undisturbed Shio-ijima walk from Kiyomizu to Fushimi Inari; the kimonos of the locals reflect the same aesthetic value.

- Attend a Tea Ceremony: Shrike the tranquil noise of folding bamboo and matcha aroma.

- Stay in a Traditional Ryokan: Notice the tatami, the futon, and the shoji interiors.

- Explore Japanese Crafts: Visit the Nakano’s Kintsugi gallery or Saitama’s shibori workshops.

- Mindful Dining: Participate in a kaiseki meal to explore washoku aesthetics.

11. SEO Tips for Your Own Travel Blog About Japan

- Primary Keywords: Japan aesthetic, Japanese culture, tatami, wabi‑sabi, Japanese temples, Kyoto gardens.

- Secondary Keywords: Japanese architecture, Zen design, traditional crafts, tea ceremony, Japanese food.

- Content Strategy: Use engaging subheadings, bullet points, and images that evoke ma.

- Meta Description (140‑160 characters): Explore Japan’s aesthetic journey—from tatami floors to temple gardens, uncover how simplicity, imperfection, and space shape everyday life.

- Internal Linking: Connect posts on Shinkansen travel to modern Japanese design pieces.

Conclusion

Japan’s aesthetic sense is an ever‑present conversation between shape, scent, and silence. Whether one is stepping into a tatami‑lined room, wandering through a moss‑covered temple courtyard, or sipping matcha in a low‑awaiting chashitsu, the rhythm of Wabi‑Sabi, Ma, and Kanso begins to feel inevitable.

The legacy of this aesthetic is not confined to the East; it informs design, art, and everyday living around the globe. By engaging with these principles—observing the gaps, valuing the worn, and embracing the ritual approach—travelers can find a deeper appreciation for the subtle beauty that shapes one of the world’s most enduring cultures.