508 views The Decline of Japan’s Notorious Crime Families

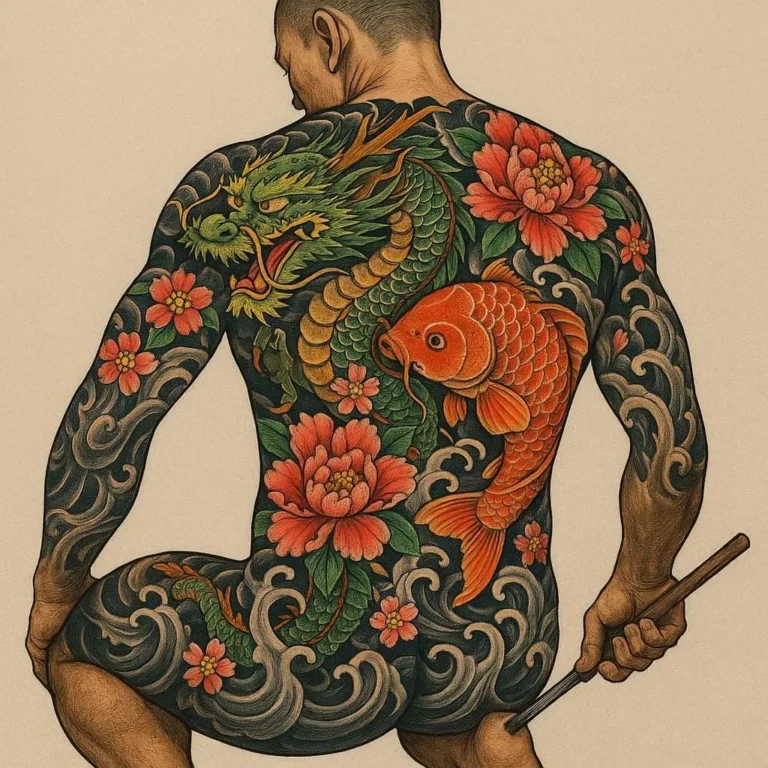

For decades, the image of Japan’s organized crime syndicates—often referred to as yakuza—has been painted in black: streets slick with ten‑year old lacquer, monks in ninkō robes, and a code that merged honor with brutality. Yet, a quiet transformation has been underway. By the early 21st century, the nation’s most infamous crime families found themselves shrinking in size, losing influence, and facing unprecedented state pressure. In this post we trace the rise and fall of these families, dissect the forces that toppled them, and examine what their decline means for Japan’s future and for global organized‑crime dynamics.

1. The Yakuza Ascendancy: Roots, Codes, and Early Power

Yakuza’s lineage can be traced back to the gamusō, or gamblers, of the Tokugawa period. In a time of strict class division, these underground gamblers cultivated a counter‑culture network that merged profit with a quasi‑monastic discipline. Fast forward to the 20th century, the yakuza evolved from gambling rings into sprawling syndicates with stakes ranging from real estate to construction, finance, and even entertainment.

Key to their early dominance was the yami noren—the practice of paying loyalists in a code that mimicked a moral obligation, often in the form of mutual protection or tribute. In an age when the state preferred a quiet circus than a violent public spectacle, yakuza act like shadow bureaucrats, filling power vacuums in local governments, handling “anonymity services” for the underprivileged, and even installing oyabun-kobun mentorship in factories where union bureaucracy stalled. The result? A deep-rooted social layer that extended into every corner of Japanese society.

2. Stakeholders in the System: Who Brought the Lawful Touch?

| Stakeholder | Role | Impact |

|————-|——|——–|

| Japanese Government | Regulated auto‑triggering the Fuka* | Upped pressure

| Law Enforcement | Tasked with enforcement of Fuka* | Strained resources |

| Local Communities | Faced extortion | Pushed for reforms |

| Media | Exposed yakuza daily | Sparking change |

|

The early 2000s offered a turning point when Japan passed the Anti‑Yakuza Act (2001), granting police the power to designate yakuza groups as “criminal organizations” and prohibiting support—financial or otherwise—from non-members. It was the first time the state stepped from passive observer to active interdiction.

3. The “Criminal Organization Designation”—A New Legal Sword

Enacting the Criminal Organization Designation Law was akin to a stern parent training a misbehaving child. The law imposed a strict membership registration; applicants had to prove their loyalties by presenting a personal shōmei certificate—a sworn document of affiliation. Failure to meet the threshold carried severe penalties, including prison terms and compulsory financial restitution.

The strategic brilliance lay in crippling yakuza infrastructure. Their operations ran on a complex web of anonymous financial accounts and shell companies—tools that are vulnerable when the trust in the network collapses. By forcing transparency, the law brought to light the amount of money laundering, coercive contracts, and labor exploitation that were previously shrouded in myth.

4. Economic Factors: Lost Markets and New Ambitions

During Japan’s economic bubble burst, many yakuza families had invested heavily in speculative real‑estate and stock markets. When the bubble collapsed, these ventures evaporated overnight. Unable to sustain their lavish lifestyles, they turned to traditional routes: extortion, prostitution, and illicit gambling.

However, by the early 2000s, global debt markets had re‑opened, enabling legitimate businesses to grow at unprecedented rates. Corporate competition tightened bidding, and these businesses began to refuse any association with the yakuza. This refusal crippled a major revenue pillar that the yakuza had relied on to finance its operations.

5. Shifting Social Attitudes: The Youth Turned Away

Post‑war Japanese society has been dynamic. The concept of “chainguardian”—the yakuza being protectors—has eroded among the new generation of students and professionals. Young people today value transparency, trust, and corporate citizenship—qualities opposite to the yakuza’s clandestine methods.

The rising prominence of internship programs and corporate apprenticeship programs left little room for binding oyabun authority. Moreover, the increasing globalization of Japanese media exposed younger audiences to other countries’ stringent law enforcement anti‑organized crime tactics—making the yakuza’s reputation a liability rather than an asset.

6. The Role of Technology: New Policing, New Weaknesses

The calculation that once pieced together ogrs (order‑growth‑revenue) schematics is now being rendered in real time through data analytics. Cybersecurity units within the National Police Agency regularly monitor keywords on social media, illegal transactions, and their own databases to detect patterns that hint at upcoming syndicate moves. AI-driven spat cells also predict where, how, and when yakuza would incite, leading to pre-emptive arrests.

Faced with surveillance that is always a few steps ahead, the yakuza lost the advantage that was essential for its initiation rituals and covert money transfers. Their once‑trusted nakama (comrades) were now under constant scrutiny, thereby eroding group cohesion.

7. International Collaboration: Japan’s Borderless Crackdown

Japan’s participation in global anti‑organized‑crime alliances (e.g., INTERPOL, United Nations Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime) has amplified the pressure. Yakuza networks are not limited to Japanese borders; they have overseas branches in Southeast Asia, the U.S., and Europe. Cooperation has enabled the tracing of cross‑border money flows, location data, and even bank account histories.

The results are twofold: 1) extradition of key leaders has disrupted command structures, and 2) the loss of internationally-backed casinos and brothels removed a vital and high‑margin business area for these families.

8. The Erosion of Traditional Revenue Streams

Beyond the core of financial influence, many yakuza families historically operated underground cultural canvases: money‑lending, student loan enforcement, black‑market drug distribution, and, paradoxically, “white‑collar” services such as corporate sponsorship of local festivals.

Most of these ventures were in direct conflict with civil law. Increased public accountability and transparent licensing abolished these symbolic ventures. The game changed: individuals no longer needed the “authentication” of a yakuza endorsement; in fact, misrepresenting yakuza backing could lead to criminal charges.

9. The Decline in Membership and the Masked Resistance

Official statistics from the Japan Justice Content Agency note a 41% decline in active yakuza membership between 2000 and 2020. The decline is even starker in Kyoto and Osaka—the traditional strongholds of factions like the Yamaguchi-gumi. Some families disagreed with new laws, but retaliation risked political backlash.

Meanwhile, a new wave of “Cyber Yakuza”—urban, tech-savvy operatives—has surfaced. They focus on hacking, phishing, and ransomware. They operate under the umbrella of organized crime but do not fit within the old code. The police began treating them under cyber‑criminal statutes, causing a shift in focus toward digital operations and away from old‑school street gangs.

10. The Societal Impact: Victims, Communities, and Culture

Communities that once feared yakuza patrol, now experience a rise in transparency. The drug‑stark neighborhoods of Shibuya and Nippori have seen new community policing models, with local volunteers and municipalities collaborating. Former yakuza corralling ex‑members now focus on rebuilding lost trust.

Toxic legacies—such as kakuji, the system where yakuza take money from marginally‑employed community members—have been investigated extensively. The process illustrates that while the yakuza’s decline drains the economy, it also allows the transformation of social bonds, giving rise to newer, healthier mutual aid networks.

11. What the Decline Means for Global Organized Crime

Japan’s path to dismantling organized crime is emblematic of the modern anti–yakuza movement worldwide. Global criminal networks that rely on established (and secretive) socio‑economic circles are forced into the shadows. Law enforcement can use Japan’s data to forge international policies. The lessons are clear:

- Designated Proper infrastructure and legal grounds dismantles visible power.

- Digital tools and data analytics outpace traditional criminal logic.

- Coordinated foreign policy reduces cross‑border influence.

- Shifting culture reduces the social capital that supports syndicates.

These aspects provide a replicable template for tackling cities where the “old guard” is entrenched.

12. Looking Ahead: Prevention, Rehabilitation, and Economic Growth

The banning of yakuza associations will not occur overnight, given certain loopholes. Activities such as co‑op organizations and shrine management remain fertile ground for subtle reinvention. Governments and NGOs need to nip in while they still have policy winners.

Rehabilitation programs for former yakuza members are vital, yet the stigma remains. Some propose a “second‑chances” law encouraging ex‑members to invest in public infrastructure. The hope is that people use their extensive networks for societal good—closing the loop of former crime to public work.

Economic growth can be accelerated through transparent governance and the injection of capital into local community projects. Lessons are déjà‑vu from micro‑finance success in the United States, where former monopolists turned into community bankers.

13. Conclusion: From Shadows to Silence

Japan’s notorious crime families have been on an irreversible slide for at least two decades. Their decline is not merely the artifact of a few bold laws, but rather a convergence of economic realities, sociocultural shifts, technology, and a global commitment to enforce uprightness. While yakuza may still exist in the margins, their influence on everyday life has turned from a looming threat to an ever‑diminishing memory.

In the grander scheme of global organized crime, Japan’s decline stands as an exemplar—one that underscores the power of policy, enforcement, and cultural evolution. For cities around the world looking to balance tradition with modernization, Japan’s Tango is a reminder that the old can fall without sacrifice, and new beginnings can arise from the ashes.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. Are yakuza still present in Japan?

Yakuza still exist but are increasingly marginalized, with fewer members and limited influence.

2. How does Japan enforce anti‑yakuza laws?

Through financial monitoring, legal designation, prison sentences, and support for community policing.

3. What industries were most impacted by the yakuza’s decline?

Real estate, construction, gambling, and some entertainment sectors were heavily affected.

4. Will yakuza families ever regain power?

It is unlikely under current conditions. The modern economy and global cooperation provide strong deterrents.

5. How can other countries follow Japan’s lead?

Implement strict designation laws, pursue technological enforcement, engage in cross‑border cooperation, and invest in social programs to heal the affected communities.