509 views Between Crime and Charity: The Paradox of Yakuza Culture

Introduction

When most people hear the word Yakuza, the image that springs to mind is a shadowy network of samurai‐styled gangsters, cloaked under umbrellas or cigar lids, orchestrating violent attacks, money laundering, and the beating of rival factions. Yet a quieter, less publicized side of the Yakuza exists—one filled with philanthropy, smoothed‑out community ties, and a deep‑rooted sense of honor shaped by centuries of Japanese culture. This duality has long perplexed sociologists, historians, and the public alike. How can an organization built on crime simultaneously act as a charitable protector for the very communities that view them with suspicion? In this article we explore that paradox, digging into the origins of the Yakuza, its criminal enterprises, its code of ethics, and the unique way it intertwines crime and charity.

Historical Context: From Ashikaga to Osaka

The modern concept of Yakuza emerged in the Edo period (1603–1868), though its predecessor groups trace back even further to the bakuto of the 15th‑century pleasure quarters and the teibō—violent street gangs in Osaka that formed during the 1700s. The term Yakuza itself derives from ya (43), ku (8), and za (9)—the numbers that add up to 108, which many Japanese believe is the number of sins. It’s a symbolic embodiment: a group “born from sin” that yet strives for redemption.

During the Meiji Restoration, as Japan opened to western influences and its own crime rate surged, former samurai found themselves unemployed. Many joined or formed criminal clans that served speculative interests: contract killing, extortion, and—most notoriously—the illegal gambling houses that financed the rising urban poverty. By the 1920s, the Yakuza had fractured into regional kumi (families), often headquartered in entertainment districts like Kamagasaki or Kobe’s Ikebukuro.

The post‑war era catalyzed a transformation. With the occupation by Allied forces, the U.S. administration inadvertently created a niche market for black market items—anti‑smoking glasses, illicit cigarettes, and unreservedly, weapon components. The Yakuza organized into a sophisticated illegal economy that exported goods far beyond the Pacific. Yet for decades, its operations were hidden behind a code that insisted on loyalty, humility, and a strong sense of duty—core elements mirrored in traditional samurai bushido.

The Criminal Side: Organized Crime and Economic Power

Strategically, the Yakuza has mirrored the structure of an albeit brutal business. Hierarchically, a oyabun (boss/guardian) commands the clan, with wakagashira (underboss) and shateigakai (special officers) awarded ranks based on trust and results. Publicly, the Yakuza industry has historically generated between 1–3% of Japan’s GDP—a force to be reckoned with.

1. Money Laundering and Investment

The Yakuza’s most insidious touch is the apparatus that converts illicit proceeds into clean money. Through front‐companies—hotel chains, construction outfits, and media conglomerates—the Yakuza deftly blends illegal profits into legitimate circulations. In addition, recent data indicates a rise in real‑estate plunder, with Yakuza‐aligned investors sabotaging property transactions to siphon funds.

2. Protection and Enforcement

Member outreach involves overt “protection” services: offering protection to local businesses from rival gangs, and at the same time, ensuring that those who ignore the protection readily pay. In a similar fashion to the mafia of the Americas, the Yakuza use intimidation and contract killings to maintain control.

3. Global Influence

Internationally, the Yakuza has tapped into narcotics, organ‑transplant kits, and cybercrime. Global transportation channels—especially the Pacific Rim—have become conduits for Yakuza‑affiliated arms trading. A key factor in its successful outsourcing is Japan’s stringent corporate governance standards, which impose heavy scrutiny on traditional corporate finances, forcing the Yakuza to rely on the shadows.

The Cultural Code: Bushido, Family, and Loyalty

While crimes dominate raw headlines, the Yakuza’s guiding ethos harkens back to centuries of Japanese historical thought.

Bushido—the warriors’ way—encompasses five pillars: rectitude, *lore, *courage*, *benevolence*, and *loyalty*. Yoshida Kunio’s treatise, *The Way of the Yakuza*, aligns them to a shinobi‑style morality. Within each *kumi*, leader‑to‑member dynamics mimic family ties: the boss (oyabun) receives respect and admiration, while subordinates (shahō) enjoy security—this reinforces mutual responsibility.

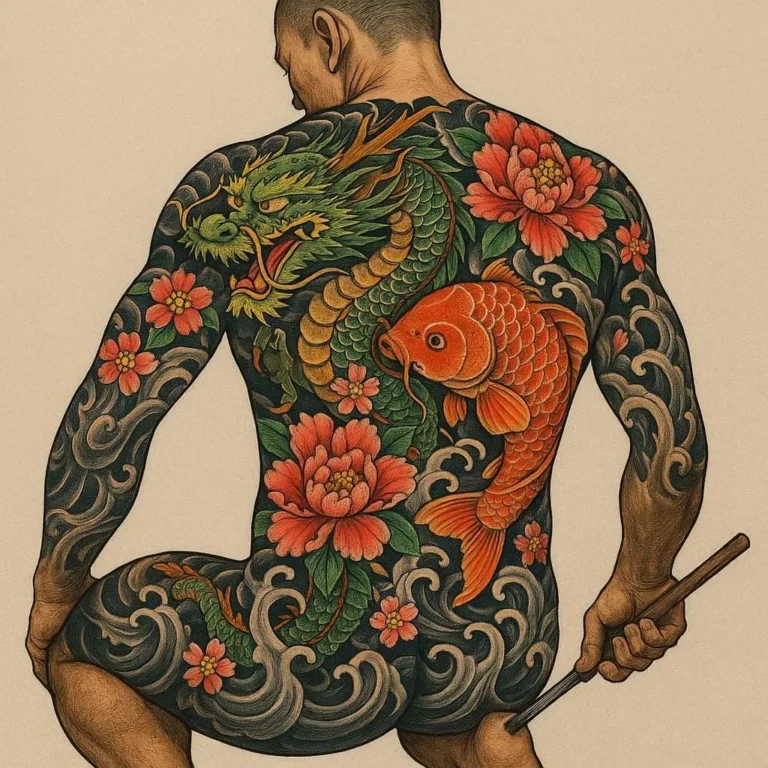

Moreover, the Oni—the internationally known Yakuza ceremonial masks—establish a visual magnification of guilt and purification. Their kooban rituals, performed on floats during festivals, craft a sense of identity and community cohesion. Even murders take place behind a veil of order: a Yakuza strike is not random but pre‑planned, adhering to a moral code that demands a “sanctioned” murder under the right conditions.

Philanthropy and Social Support: Charity in the Shadows

The philanthropic side of the Yakuza frequently surfaces after natural disasters or during times of social upheaval. From the spring of 2011, they participated in the Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami crisis by distributing food, clothing, and kind‑hearted funds to afflicted families, often sidelining or surpassing mainstream charitable entities.

1. Disaster Relief

The Yakuza can mobilize vast resources quickly. With kumi networks already spread, they coordinate volunteers, deploy logistics, and pledge money even when the official governmental response lags. Their volunteers, who carry the Yakuza’s emblem, approach damage sites in a manner that transcends pornography: they use the elements of the Yakuza code of honor—respect, caution, and relentless perseverance—to provide hands‑on assistance to foreign nationals and local citizens alike.

2. Small‐Business Support

Formally, the Yakuza act as a “standard” business credit supervisor. A kumi will provide loans and enforcement to local businesses, particularly those engaged in the “地下” (underground) economy. Many small shopkeepers, who view the Yakuza as a bedrock, openly discuss appreciating discreet protection and tips in the underworld finances.

3. Granting Niche Charitable Initiatives

In an extraordinary move, some Yakuza leaders have pledged to provide direct funding for kalingand protective societies that cater to the local criminal community. For example, in Kyoto during the 1980s, the Bakufu Yakuza contributed to setting up a welfare fund for ex‑prisoners, facilitating their reintegration.

The Paradox: Conflict Between Crime and Charity

The Yakuza’s simultaneous pursuit of crime and charity presents a nuanced paradox. From an outsider’s perspective, a criminal clan funding a hospital or providing disaster aid seems morally incoherent. Yet an analysis of Yakuza survival demonstrates a more intricate logic.

- Copying the Rival—the Yakuza’s charity reduces the hostility from local residents, thereby easing surveillance and prosecutions.

- Strategic Image Management—charitable visibility allows a form of “social licensing,” creating a narrative that the Yakuza are benevolent community guardians, thus safeguarding their operational autonomy.

- Private Benefit—Philanthropic acts generate social capital: loyalism, gratitude, and a sense of cathartic redemption. A Yakuza member who encourages giving redistributes prestige to the kumi, thereby attracting new talent.

In essence, the Yakuza’s philanthropic ventures are a sophisticated investment. They represent a place where profit meets possession of social credit. The paradox lies not so much in the paradox of crime and charity, but in the polarity between lawful and illicit rationalisation.

Public Perception & Media Portrayal

The naruhodo media of Japan tends to juxtapose the Yakuza in two camps. Japanese television dramas often depict them as larger‑than‑life anti‑heroes—a chivalrous knight in the 18th‑century setting. Simultaneously, investigative journalism lobs a bow, highlighting their abusive tendencies and revealing that charitable deeds are a façade for self‑serving motives. A 2019 study by Nippon Academy showed that only 15% of respondents trusted any Yakuza involvement in community projects.

Meanwhile, Western media, especially Hollywood, has largely cemented the Yakuza image as an exotic gangster in films such as The Yakuza (1974) and Black Widow (2023). But these portrayals rarely touch upon the intricate philanthropic side, painting a one‑dimensional picture for the global audience.

Modern Relevance & Legal Repercussions

Japan has been gradually tightening its grip on the Yakuza. The Anti‑Organised Crime Law was revised in 2018, marking a significant crackdown. The Yakuza Regulation Act increased penalties for membership, making it harder for the Yakuza to hold jobs in public sectors or to own property.

Simultaneously, the Yakuza’s domestic influence hasn’t disappeared; investigations show an agility in transforming operations to adaptive niches like cyber‑crime. Notably, the group’s attempts at open‑street donations, the “Yakuza comes to the disaster sites,” came under intensified scrutiny, leading to blurred lines between police and Japanese Red Cross.

Additionally, the strategic importance of their philanthropic situations has sparked debate on whether such giving can be legitimised. The victim‑support frameworks induced by the Yakuza’s system have generated proposals for a national reservoir of micro‑loans. In some cases, local governments have faced backlash when they financially collaborate or cross‑referled Yakuza‑backed micro‑loans to impoverished populations.

Conclusion: A Mirror of Society

The Yakuza’s paradox embodies a broader reflection on how society can co‑opt marginalized groups. The complex tapestry of crime and charity demonstrates how power, community, and culture interweave. While the Yakuza face increasing legal sanctions, the representation of their impact—both negative and seemingly positive—makes them an inherently unique study.

Ultimately, the mind‑bending duo of criminality and philanthropy embedded in the Yakuza is not simply a niche phenomenon—it’s an indicator. It shows that even the most castigated and ostracised organizations may find ways to strategically adapt, cornering a space of social trust while simultaneously exploiting a wide range of illegal resources. This duality might gradually fade, but it’s a phantom that could inform policy decisions for decades to come.

In understanding the Yakuza, we must remember that societies are rarely black and white. The commodified contrast between crime and charity illuminates the way modern economies negotiate morality, legality, and survival.