508 views The Sound of Shakuhachi: How Japan Found Poetry in Bamboo

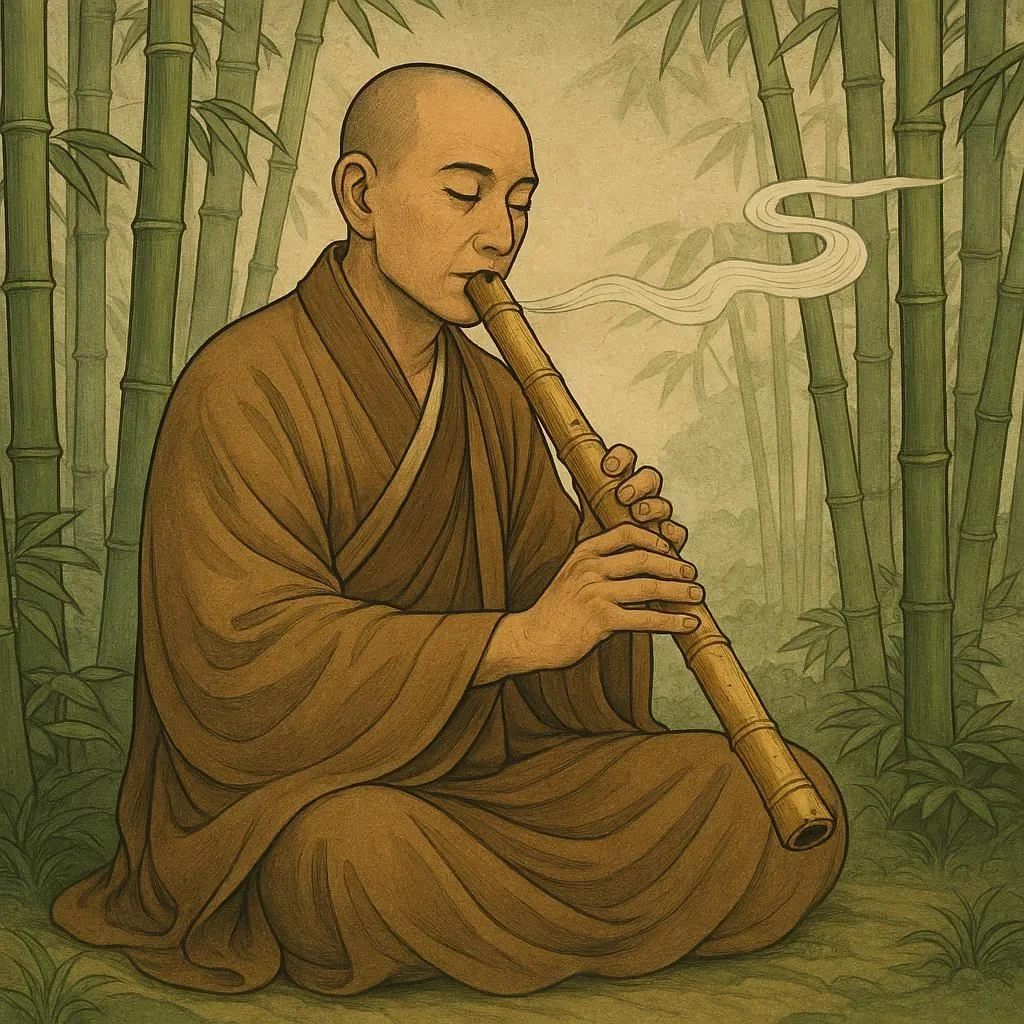

When the wind slips through a bamboo grove, it whispers tales older than any written chronicle. In Japan, the shakuhachi—a slender, bamboo flute—has become a living poem, resonating with centuries of devotion, spiritual practice and artistic expression. This post explores the history, construction, cultural impact, and modern renaissance of the shakuhachi, inviting you to discover why the delicate breath is more than a musical note: it’s a bridge between humanity and nature.

1. The Origins of the Shakuhachi

The earliest shakuhachi traces back to the 12th century, brought to Japan by Buddhist monk monks who had encountered bamboo flutes while traveling in China and Korea. Originally traded as shakuhachi (扇筒), a term meaning “a long flat bamboo pipe,” the instrument quickly adapted to Japanese aesthetics. The iconic 13‑inch body was lengthened to 17 inches in the 15th century, giving it the resonant, haunting tone we recognize today.

For samurai warriors and monks alike, the shakuhachi was a tool of discipline. Mingei folk artist Sen no Rikyu valued its raw beauty, and it was later linked to the shinobi, or ninjas, often using it as a covert signal in the forests of feudal Japan. By the Edo period, the shakuhachi had gained a dual reputation: a lacquer‑lined instrument for court music—gagaku—and an instrument for solo meditation—honkyoku—painted in select artisanal workshops.

2. Bamboo, Craft, and Sound

2.1 Key Materials

The core of a shakuhachi is a single piece of bamboo, typically Moso bamboo (Phyllostachys nigra). The reed is painstakingly selected to ensure that a subtle variation in thickness and moisture balances the overtones. Prolonged exposure to climate, humidity, and temperature in the barrels—where the bamboo ages for months—affects the instrument’s pitch and timbre.

2.2 The Craftsmanship Process

- Selection and Cutting – The craftsman logs the bamboo’s natural growth rings, choosing a flat section without cracks.

- Drying – The bamboo is slowly dried to 10‑12 % moisture content, a complicated process that can take up to six months, ensuring it will not warp.

- Lacquer Coating – A thin layer of lacquer, often tsuba (樽色), strengthens the body while providing a distinct dark finish.

- Bracing and Fining – After drilling holes, the player’s breath includes the lamination of small felt or paper layers to buffer the tonal quality.

The final product is a breath‑controlled, elegant 17‑inch flute capable of producing an expansive range of microtones, including muten—the subtle silence that sits between notes.

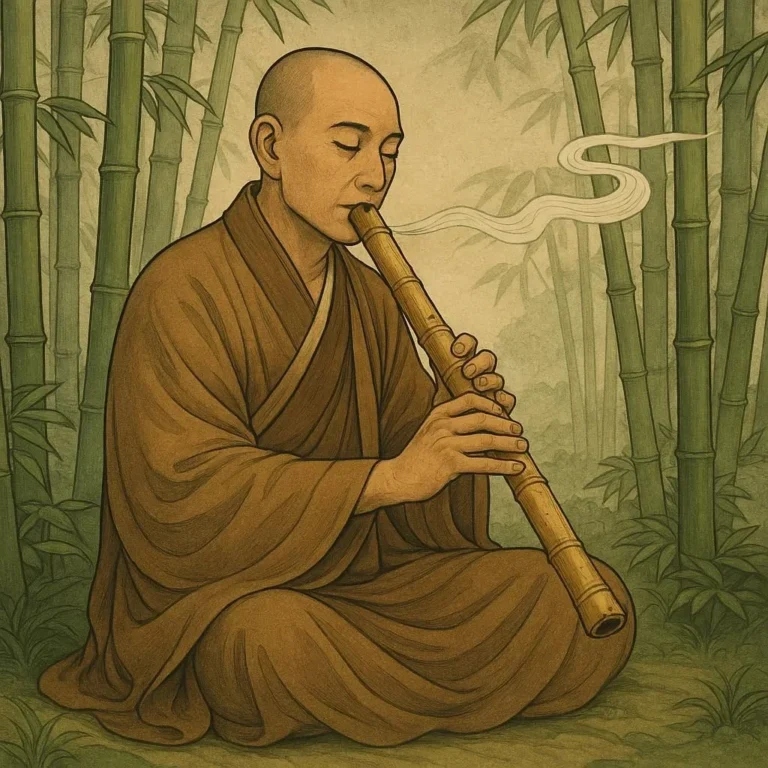

3. Playing Techniques & Meditation

3.1 Classical Honkyoku

Honkyoku (original music) were composed for forest meditation, sitting in silent caves with fans—kuzushi—to create echoing soundscapes. Such compositions utilize fu (fast) and mei (soft) cuts, a natural phrasing that mirrors breathing. The goal is not to please an audience but to align the mind with anicca—impermanent reality.

3.2 Modern Performance

Contemporary musicians fuse honkyoku with jazz, rock, and even electronic soundscapes. Foundational techniques such as kiai (blow with force) and kōkō (extended overtones) allow for expressive expansion beyond traditional boundaries.

3.3 Mind‑Body Connection

Playing the shakuhachi is a meditative exercise. Musicians breathe slowly, focusing on inhale‑exhale rhythms that induce zazen – seated meditation. The fluid scoring of notes encourages a meditative replay of nature’s elements—leaves spiraling, raindrops, and so on—providing acoustic mindfulness.

4. Cultural Significance

4.1 Buddhism & Shinto

The shakuhachi’s prominence in Zen Buddhism cannot be overstated. Rehearsing koan (paradoxical puzzles) is practiced as a sonic discipline. In Shinto rituals, the flute’s pure timbre is believed to invite kami (spirits). The ryū (school) of Noh theatre used the shakuhachi for opening ha—a spontaneous prep to immerse audiences.

4.2 Modern Media

From films such as The Last Samurai to modern pop hits “Kokoro” by Kenji‑Yamada, the shakuhachi’s voice has become ubiquitous. The soundscape became integral to anime works like Spirited Away by Hayao Miyazaki, forging a bridge between traditional heritage and contemporary storytelling.

5. The Global Revival

In the 20th century, the world’s musicians sought to learn from the shakuhachi’s minimalist “less is more” philosophy. Claude Debussy hinted at the instrument’s influence in “Clair‑de‑Lune” with its airy, sustained notes. In 1975, the Shakuhachi International Society established in California did more than host festivals; it taught Western players how to tap into the instrument’s muten.

The online realm now offers masterclasses from renowned players such as Seiji Yasushi, Iwao Takada, and Eijun Kogawa, who all share insights: “Pick a bamboo with serenity. Listen to the whisper of wind.” These resources have helped produce cross‑disciplinary collaborations—shakuhachi with electronica, classical piano, even spoken-word poetry.

6. How to Learn the Shakuhachi

Although the instrument is relatively simple visually, mastering it demands dedication. Here’s a beginner’s roadmap:

- Choose the Right Instrument – Start with a standard just‑in‑time scale of 13–14 inches before progressing to the 17‑inch model.

- Fundamentals of Breath Control – Practice diaphragmatic breathing to maintain steadystated tone.

- Basic Finger Positioning – Map out your thumb, index, middle finger, and pinky positioning across the holes—matching mind to body.

- Explore Muten & Silence – Learn to create micro pauses; these are as vital as the tunes themselves.

- Zone in on Tuning – Use a digital tuner; listen for the subtle overtones.

- Anime Pod – Record your solo; it’s essential to realize how your sound merges with any setting.

Commit to daily fifteen‑minute repetitions, noting the change in breath and expression. A course from Japan’s Shakuhachi Isshu Hall can enrich learning, converting knowledge into a practiced, purposeful art.

7. The Future of the Shakuhachi

While rooted in centuries, the shakuhachi evolves with technology. Modern recordings embed binaural audiography, giving listeners the feeling of upside‑down forest breezes. Fusion projects in 2024 attempt to match sound‑scapes with AR visuals, enabling audiences to “taste” the wind.

Preservation remains crucial. The Global Intangible Cultural Heritage roster by UNESCO includes The Musical Culture of Shakuhachi, ensuring future generations remain taught. Workshops across the Pacific—Kuala Lumpur, Toronto, Sydney—continue to bolster a global community trained in broader musical dialogues.

8. Conclusion

The shakuhachi does more than glint in concert halls. Its bamboo vessel houses a philosophy: how the mind can echo the quiet, how breath can become poetry, and how fleeting moments—like a single note—can linger in the heart. So the next time you hear a delicate hush, imagine the wind in a bamboo grove shaping that sound, reminding us that the most subtle vibrations often carry the most profound stories.

Key Takeaways

| Topic | Summary |

|——-|———|

| History | 12th‑century roots, adopted by Zen monks and samurai. |

| Craftsmanship | Moso bamboo, lacquer finish, micro tuning. |

| Cultural Role | Buddhist meditation & Shinto rituals. |

| Modernity | Global collaborations, tech integration. |

| Learning | Breath control, muten, steady practice. |

Embrace the shakuhachi, and awaken poetry in every breath.